Dutch sociologist and documentary photographer Lieke Nieuwenhuizen visited Curuinsi Huasi in the Santa Sofia indigenous reserve to learn more about the Community-based turtle conservation program in the Amazon River that FBC supports since 2008.

As a result, she published a note full of insights and reflections about culture, conservation and tradition. I hope you enjoy it as much as we did.

****

Between tradition and modernization: the indigenous communities of the Amazon and their struggle to preserve cultural heritage

About the Author: Lieke Nieuwenhuizen is a documentary photographer, sociologist, and storyteller. Her experiences of independence, emancipation, and feminism have deeply shaped her identity and the way she sees the world. With a background in Human Resources, Diversity & Inclusion, she is passionate about understanding people and the structures that shape societies. Driven by curiosity and a love for exploring the world, she seeks to amplify diverse voices and foster deeper connections across cultures. You can read more about her and her work on: Home | The People Perspective

I am traveling in Colombia for three months now, but I haven’t ventured into the Amazon jungle yet—at least, not in this country. There’s something about the jungle that always draws me in. I loved my time in Madre de Dios last year in Peru—the vast rivers, the dense green, the thick, humid air. So I decide to go to Leticia, where the Amazon weaves its way between Colombia, Brazil, and Peru. From Leticia, I take a boat to Santa Sofía, a small village between Leticia and Puerto Nariño.

As I step off the boat, barefoot, I hold my camera and laptop above the water to keep them dry. I meet Elisvan, my guide for the upcoming days. Elisvan is cutting a path through the dense greenery with a machete, and I follow closely behind. We’re on our way to the community, were several indigenous groups living together deep in the Amazon. Here, traditions are upheld that have been passed down from generation to generation for centuries. But how much longer will that last?

A multi-ethnic world in the heart of the Amazon

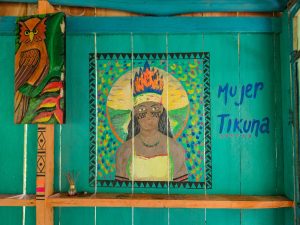

The Amazon in Colombia is home to 52 different indigenous communities, each with its own language, traditions and way of life. Santa Sofía, where I am, is a multi-ethnic village where the mostly Tikuna live, or Magüta as they are now self-named, in a process of separation form white-assigned names.

“The biggest differences between the communities are in the language and the way of thinking,” says Elisvan, my guide and inhabitant of the village. “For the TiKuna, tobacco is the sacred plant, while for us it’s ayahuasca. Each plant has its own rules, but none is superior, a deep respect for nature unites them all.”

One of the most pressing concerns for these communities is the conservation of their environment and its wildlife. Over the past few decades, the population of three globally endangered species of turtles in the region has plummeted due to overexploitation and habitat loss.

This alarming decline led to the founding of the Curuinsi Huasi project under the leadership of the traditional healer and leader Abuelo Rogelio Carihuasari and other members of the El Progreso, Nuevo Jardin and Santa Sofia community. Recognizing the cultural and ecological importance of turtles, the Kokama, Tikuna, and Yagua groups initiated discussions on their protection and sought support from Fundación Biodiversa Colombia, a conservation NGO.

Conservation and spiritual connection

The indigenous communities are working hard to protect their environment. The El Viejo Bosque Reserve is an initiative of Curuinsi Huasi, which sought the support of other communities to make it a reality. It focuses on reforestation and environmental education. Indigenous communities follow a strict philosophy: “For every tree we cut down, we plant ten.”

Another important project is the protection of the turtles, which plays a sacred role in Tikuna rituals. Maria Nené Angarita has been working on turtle conservation for 13 years and remembers how their numbers drastically declined due to over-exploitation. “When we started in 2008, we could only release 20 baby turtles. Now, we protect 300 mothers each year on five river beaches.”

“Even now, we still need resources to continue our work. We protect and monitor the turtles at night, as they follow a strict schedule. The work is done in night shifts, with volunteers guarding nests and recording eggs. The Taricaya emerges between 7 PM and 10 PM, and again from 2 AM to 6 AM. The Charapa only comes out at midnight. Our job is to guard them, track their nests, and ensure their survival. Knowledge passed down by elders has been vital in this endeavor, teaching conservationists how to recognize nests, measure eggs, and mark their locations. Each released turtle is named, and the location where it was found is carefully recorded.”

“To do this work, we need proper clothing and protection—boots, long-sleeve shirts, hats, and plastic tents to shield us from the strong wind and sand. But support is limited.”

This heritage, passed down by the elders, is now being taught to the next generation. “Our children need to see the turtles as we did,” says Maria. One of the ways the community preserves this connection is through the annual Turtle Festival held every November. The entire community comes together, and they invite neighboring communities from the Brazilian and Peruvian sides of the Amazon to join in the celebration. Through this gathering, they aim to educate the children and raise awareness about the beauty and importance of these remarkable creatures.

In the conservation effort I had with Elisvan during my time there, we had the privilege of releasing three baby turtles into the mighty Amazon River, allowing them to grow and thrive in their natural environment. It was a symbolic and hopeful moment, representing the ongoing efforts to restore balance to the ecosystem.

La Pelazón: A rite of passage

One of the most important rituals within the Tikuna community is La Pelazón, a ceremony that prepares young girls for adulthood. This tradition, which has disappeared in many areas, is still carried out in some communities.

At the age of around 12 or 13, when she has her first menstrual cycle, a girl begins a phase of isolation that can last from months to years. During this time, she is mentored by older women, who teach her essential skills like weaving, medicinal plants, and farming. This preparation for adult life ends with a big celebration, where the community comes together to mark her transition.

Symbols like the taricaya (the Yellow-spotted River Turtle) play an important role in the ceremony. The turtle shell is carefully dried and turned into a musical instrument, which accompanies the ritual dances. The community gathers in the maloca, a large traditional house, where they sing and dance for days. The girls receive new names and wear crowns, while shamans bless them with strength and wisdom.

Alexis, the father of a 12-year-old girl, sees the value of this tradition: “If we don’t carry out this ritual, there could be spiritual consequences. Our ancestors believed that if we don’t, spirits will appear as a warning.”

However, he also acknowledges that the modern world has influenced these practices. His daughter attends school and was unable to remain in isolation for a full year, as was once the norm. Instead, her ceremony lasted six months because Alexis and his wife decided they did not want to take her away from school for that long. This reflects how the community is adapting, striving to balance tradition with modernity.

Yet, even with these adaptations, this process raises important questions for me. Why is it only girls who must go through such an intense period of isolation? Where is the equality in this tradition? Why is there no expectation for boys to undergo an equally demanding rite of passage? If education is one of the most powerful tools for building a more equitable society, how does this practice fit into that vision?

And while I recognize the deep cultural significance of these traditions, I can’t help but wonder: should the preservation of heritage come at the cost of gender equality? Even within Indigenous communities, where traditions are deeply rooted, perhaps it is worth reflecting on and reconsidering the roles that reinforce inequality.

The impact of modernization on indigenous cultures

While the Tikuna hold on to their traditions, they also see how technology and modernization are affecting their community. Maria Nenea Garita, a woman from Santa Sofía, and chairlady of the guardians of the turtles, recalls a time without phones or engines: “We used to go from house to house to spread news. Now, people send messages and visit each other less.” Language loss is one of her biggest concerns. “Our children no longer speak Tikuna fluently,” says Maria. “They learn Spanish in school and become more and more disconnected from our culture.”

The rise of mobile phones is a double-edged sword. Alexis has decided not to give his daughter a phone until she reaches the tenth grade. “It changes the way kids think. They find it very attractive, and they constantly want to check things online, on Instagram and YouTube, which can be a bit harmful. They get distracted and lose sight of their cultural values.” However, he acknowledges that technology can also be helpful, especially when it comes to staying in touch while his daughter is at school in Leticia.

Back in Leticia, I come across a mural that captures my attention. It resonates with me because it seems to make a powerful statement about indigenous identity, perception, and modernity. The artwork challenges historical prejudices, celebrates indigenous resilience, and invites reflection on the intersection of tradition and contemporary life. I am deeply moved by their message and, with humility and respect, I feel in alignment with this statement.

The word salvaje has long carried a colonial, derogatory meaning, used to label indigenous people as uncivilized. Yet in this mural, it feels reappropriated, a reclamation of identity. It highlights how indigenous communities have been categorized over time, culminating in the word humano—a simple yet profound statement affirming their humanity above all else.

It reminds me of my intention during this trip—and in all my travels—to listen carefully, to be aware of the lens through which I see the world, and to resist the urge to impose my own perspectives onto what I encounter. I don’t always succeed, but I truly believe that the key to understanding one another lies in listening without prejudice.

A struggle for preservation, but also for the future

Despite the challenges of modernization, the Tikuna community remains determined to continue their traditions. Organizations like Curuínsferarbe@fundacionbiodiversa.orgi Huasi are working on statutes and “life plans” to protect indigenous autonomy and cultural identity. But the future remains uncertain. While elders like Maria and Alexis fight to pass on knowledge, technology threatens to distance the younger generation even further from their roots. “We have to keep talking, keep sharing,” says Maria. “If we don’t, our traditions will disappear with us.”

As these communities continue to fight for their cultural and environmental survival, their resilience and dedication remain unwavering. The protection of the Amazon is not just about preserving biodiversity but also about safeguarding centuries-old traditions and knowledge systems that hold invaluable wisdom. With ongoing support and awareness, the dream of a thriving Amazon, rich in both cultural heritage and ecological diversity, remains within reach.